A fruit seller stands with his pushcart in front of an Urdu literature bookshop in Urdu Bazar in Delhi’s old district on October 14, 2024. -AFP

A fruit seller stands with his pushcart in front of an Urdu literature bookshop in Urdu Bazar in Delhi’s old district on October 14, 2024. -AFP

Indian bookseller Mohammed Mahfooz Alam, one of the few remaining people selling literature in a language poets have cherished for centuries, sits desolately in his small shop in the busy center of Old Delhi.

The rich history of Urdu, spoken by millions of people today, illustrates how different civilizations came together to create India’s complicated history.

But its literature is immersed in the cultural dominance of Hindi, struggling with the false perception that its elegant Perso-Arabic script makes it a foreign import and a language of Muslims in the Hindu-majority country.

“There was a time when we would see 100 books published in a year,” says 52-year-old Alam, who laments the loss of the language and readership.

The narrow streets of the Urdu Bazaar, in the shadow of the 400-year-old Jama Masjid, were once the core of the city’s Urdu literary community, a center of printing, publishing and writing.

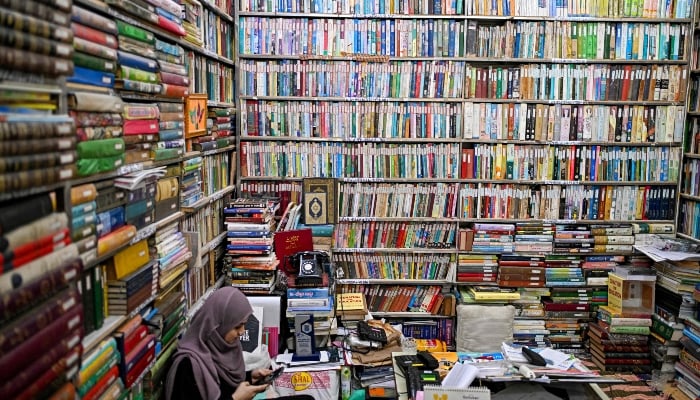

This photo, taken on October 22, 2024, shows a student sitting amid stacked Urdu books at Hazrat Shah Waliullah Public Library, in Urdu Bazar in Delhi’s Old Quarter. —AFP

This photo, taken on October 22, 2024, shows a student sitting amid stacked Urdu books at Hazrat Shah Waliullah Public Library, in Urdu Bazar in Delhi’s Old Quarter. —AFP

Today, the streets, once lined with Urdu bookstores, packed with scholars debating literature, are now full of the aroma of sizzling kebabs from the restaurants they replaced.

There are only half a dozen bookstores left.

“Now there are no takers,” Alam said, waving to the streets outside. “It’s a food market now.”

Dying ‘from day to day’

Urdu, one of 22 languages enshrined in India’s constitution, is the mother tongue of at least 50 million people in the world’s most populous country. Millions of others speak it, as well as in neighboring Pakistan.

But while Urdu is largely understood by speakers of India’s most popular language Hindi, their scripts are completely different.

Alam says he can see Urdu literature dying “day by day”.

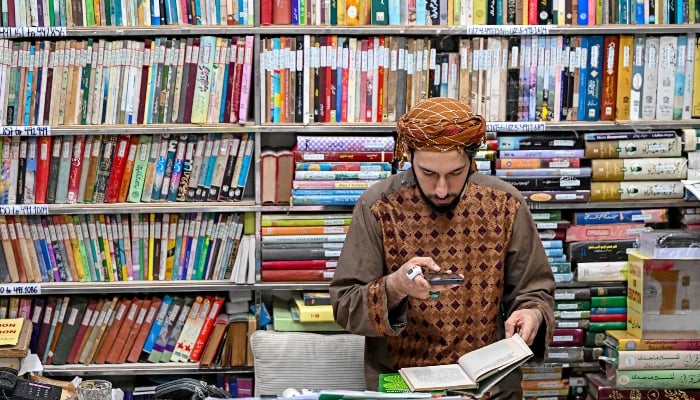

A student taking photos of an Urdu book at the Hazrat Shah Waliullah Public Library, in Urdu Bazar in the old district of Delhi on October 22, 2024. -AFP

A student taking photos of an Urdu book at the Hazrat Shah Waliullah Public Library, in Urdu Bazar in the old district of Delhi on October 22, 2024. -AFP

The Maktaba Jamia bookstore he manages opened a century ago. Alam took over this year, driven by his love for the language.

“I’ve been sitting since morning and barely four people have come,” he said somberly. “And even those were college or school-age kids who wanted their textbooks.”

Sharing the roots of Hindi and blending words from Persian and Arabic, Urdu emerged as a hybrid speech between those who came to India through trade and conquest – and the people among whom they settled.

But Urdu has faced challenges because it is seen as linked to Islamic culture, a popular perception that has grown since Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s Hindu nationalist Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) came to power in 2014.

Far-right Hindu nationalists seeking to diminish Islam’s place in India’s history have opposed its use, with protests over the past decade ranging from the use of Urdu in clothing advertisements to even graffiti.

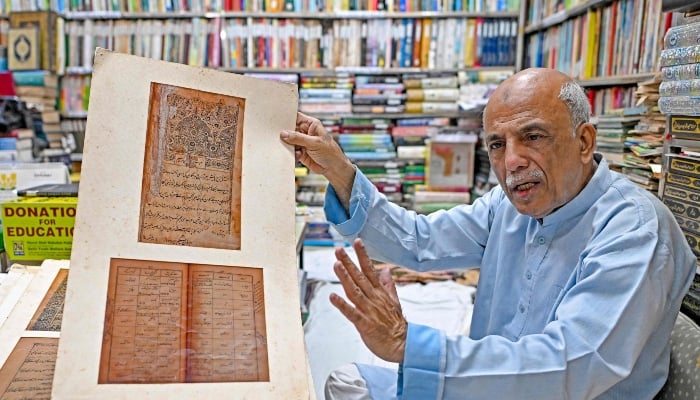

Sikander Mirza Changezi, co-founder of Hazrat Shah Waliullah Public Library, speaks during an interview with AFP at his library in Urdu Bazar in Delhi’s Old Quarter on October 22, 2024. –AFP

Sikander Mirza Changezi, co-founder of Hazrat Shah Waliullah Public Library, speaks during an interview with AFP at his library in Urdu Bazar in Delhi’s Old Quarter on October 22, 2024. –AFP

“Urdu is associated with Muslims, and that has also affected the language,” Alam said.

‘But that’s not true. Everyone speaks Urdu. You go to villages, people speak Urdu. It is a very sweet language. There is peace in it.’

‘Feel the beauty’

For centuries, Urdu was an important administrative language.

Vendors first set up shop in the Urdu Bazaar in the 1920s, selling stacks of books ranging from literature to religion, politics and history, as well as texts in Arabic and Persian.

More lucrative fast-food restaurants slowly emerged in the 1980s, but trade fell dramatically over the past decade, with more than a dozen bookstores closing their doors.

A shop owner (right) standing outside his Urdu literature bookshop in Urdu Bazar in Delhi’s Old Quarter on October 14, 2024. -AFP

A shop owner (right) standing outside his Urdu literature bookshop in Urdu Bazar in Delhi’s Old Quarter on October 14, 2024. -AFP

“With the advent of the Internet, everything became easily available on mobile phones,” says Sikander Mirza Changezi, who co-founded a library to promote Urdu in Old Delhi in 1993.

“People started thinking that buying books is useless, and this has affected the income of booksellers and publishers, and they have switched to other businesses.”

The Hazrat Shah Waliullah Public Library, which Changezi helped create, is home to thousands of books, including rare manuscripts and dictionaries.

It aims at promoting the Urdu language.

Student Adeeba Tanveer, 27, who has a master’s degree in Urdu, said the library provided a space for those who want to learn.

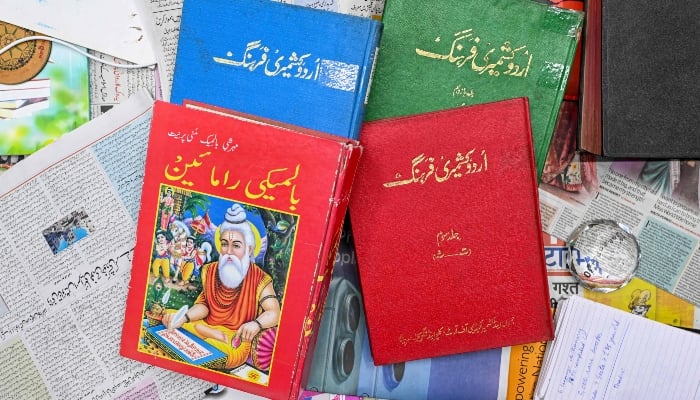

Urdu books are pictured at the Public Library of Hazrat Shah Waliullah, in Urdu Bazar in the Old Quarter of Delhi on October 22, 2024. -AFP

Urdu books are pictured at the Public Library of Hazrat Shah Waliullah, in Urdu Bazar in the Old Quarter of Delhi on October 22, 2024. -AFP

“The love for Urdu is slowly coming back,” Tanveer said AFPadding that her non-Muslim friends were also eager to learn.

“It’s such a beautiful language,” she said. “You feel the beauty when you say it.”

Leave a Reply